I Ching | Ancient Thoughts for Modern Times

Behold, one of my favorite treasures… My first copy of The I Ching, or The Book of Changes. Translation by Frank J. MacHovec, published by The Peter Pauper Press in 1971.

I found this copy of the I Ching a few years ago at The Last Bookstore in Downtown Los Angeles. At risk of sounding too predictable, I must admit that finding this bright red book felt like destiny. I tend to say and do a lot — often too much. As such, I am constantly inspired by minimalists. The ability to be understood in the most simple way possible is a genuine super power. I genuinely think that having parameters allows for a special kind of transcendence with whatever is taking place. Whether making art, making conversation, or making use of time, doing less allows for being more.

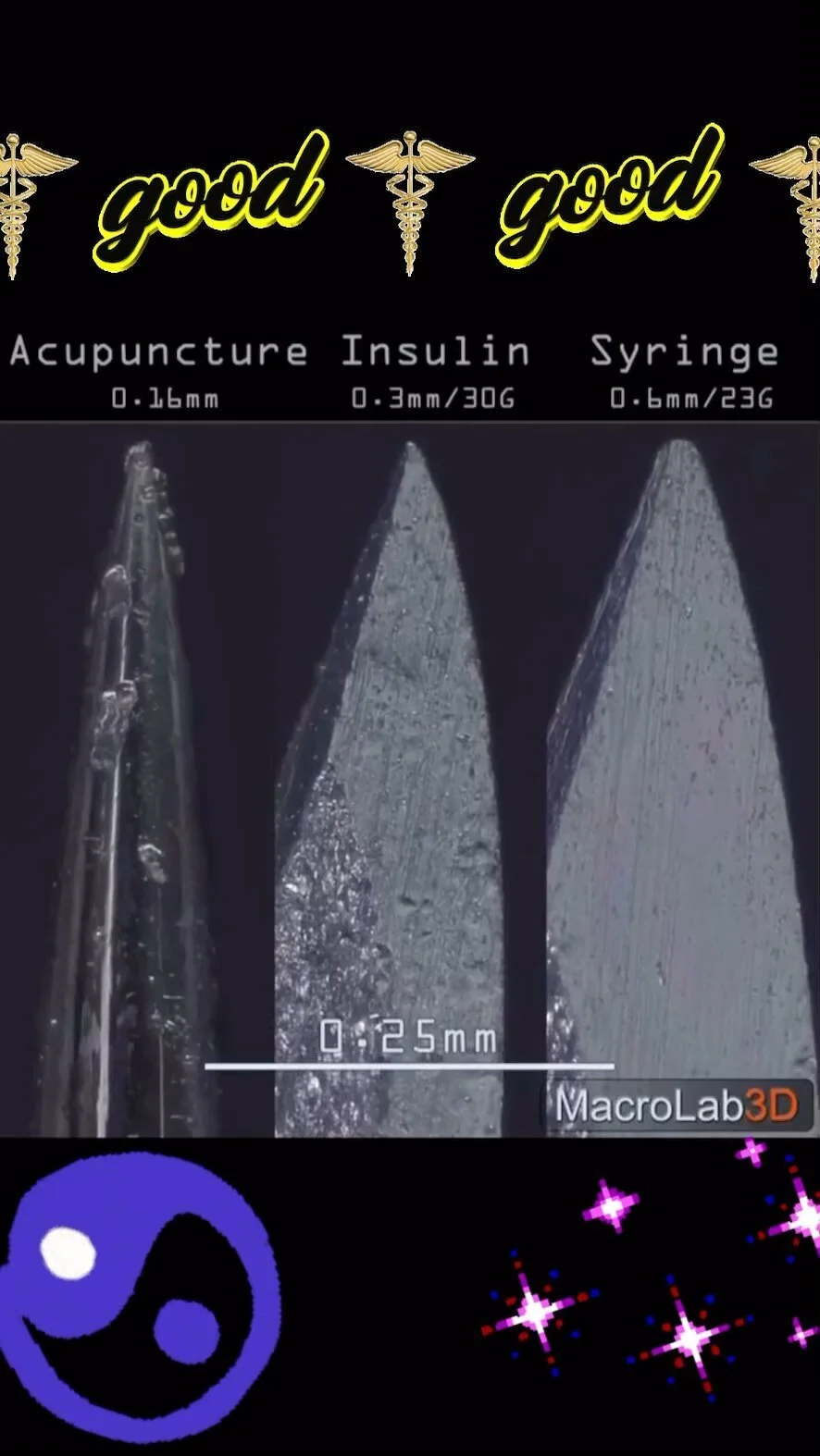

While I always make it a point to mingle with every aisle of The Last Bookstore, this particular occasion was the first visit my eyes were keen on finding Traditional Chinese Medicine books. At the time, I had recently left my career in film to move back home to California and study acupuncture and traditional medicine. Honestly, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. I’m definitely still in the wormhole but one thing I know for sure — my studies have awoken a deep personal connection with Traditional Chinese Medicine and its founding philosophies. The medicine feels familiar in ways that are hard to describe. I feel like I somehow recognize the road I’m walking on and where it’s going. It has completely refined my approach to health and my philosophy of life. In a way, both the history of Chinese medicine and my own journey with it all begins with this book: The Book of Changes.

This rare translation of the I Ching is unique in its effort to match the original intent of its manuscript: simple counsel from all available perspectives of the universe. In a way, nobody has looked at the I Ching this simply for nearly 4000 years. By keeping it simple, FJM creates space for the I Ching’s teachings to become alive in us in their own way.

I’ve had this little red book for 2 years now. However, I have only recently started to really spend time with it. To say the least, my experiences have been profound. It has cracked open a deeper curiosity about the origins of my medicine. As I dive further into I-Ching philosophy, I feel a similar familiarity with its material as I do with acupuncture and Traditional Chinese Medicine theory. I feel like I am in the exact right place at the exact right time, like everything is meant to be.

In western thought, there is a word for this : SYNCHRONICITY.

Synchronicity is the word used to “describe circumstances that appear meaningfully related yet lack a causal connection.” First introduced by psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl G. Jung, synchronicity is a concept that formulates a point of view diametrically opposed to that of causality. In his forward to Richard Willhelm’s prized 1950 translation and commentary of the I Ching, Jung wrote, “Since [causality] is a merely statistical truth and not absolute, it is a sort of working hypothesis of how events evolve one out of another, whereas synchronicity takes the coincidence of events in space and time as meaning something more than mere chance.” He continues, “just as causality describes the sequence of events, so synchronicity to the Chinese mind deals with the coincidence of events.”

To Chinese medicine and philosophy, the mysterious forces responsible for synchronicity can be communicated with, or in other words, observed and worked with. To put it simply, the I Ching is a calculator to factor in the effects of chance when making decisions. In this case, “chance” is not random — it is a part of the universe’s subconscious. And in the Traditional Chinese understanding of Microcosm and Macrocosm, the universe’s subconscious and our own subconscious is the very same. Hence, not only is the I Ching meant to reflect the laws of nature and change in the universe, it is meant to provide a language for us to communicate with our own subconscious.

In time, I look forward to sharing what it has taught me and how I have integrated its teachings. But before I do that, I feel compelled to share a little bit more about the history of the I Ching and to make the case as to why its teachings are still useful today. There is something particularly advantageous about teachings that have stayed influential to both eastern and western philosophy and psychology over millennia. We must ask ourselves… why has this stuck around so long?

Understanding the value of the I Ching is vital to its magic. The I Ching is a mirror meant to capture our true reflection. In this mirror, we are meant to see ourselves and nature as reflections of each other. When using it as an oracle, it is a way to account for “chance.” When using it for advice, it reveals a reflection of ourself juxtaposed to ordered nature as opposed to our own monkey mind. Like quotes from the Buddha embroidered on a tacky pillow, the I Cheng’s profound yet simple, practical wisdom is often overlooked without context and experience.

So, without further ado, some context and experience…

Modern Medicine with Mythical Origins

Chinese medicine and philosophy is born from legend. By that I mean our classic texts are so old that their true authors have been lost over time. Although some scholars offer historical interpretations of China’s legendary practitioners like The Yellow Emperor or Fu Xi, the mythical origins of Chinese philosophy and medicine do not take away from its practical importance and medical significance. While Chinese medicine might not be literally true, it literally works!

Chinese philosophy and Chinese medicine are directly connected. Having been developed over thousands of years in a sort of symbiotic relationship, it is useful to talk about them in parallel. By doing so, we are able to talk about the I Ching’s beginning, middle, and end at the same time, which is exactly how the I Ching is meant to be understood.

The origin of Chinese medicine emerged in the shamanistic era of the Shang Dynasty Period (1766-1122 BCE). Most Chinese philosophy and medicine as we practice them today began to form from then on, particularly during the Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BCE) and the Warring States period of the Zhou Dynasty (475-221 BCE). Sometimes considered China’s age of enlightenment, it was during this time that Chinese culture took its first high-impact dives into philosophy and science. While acupuncture, herbalism, and natural philosophy existed in some forms prior to this era, is during this time these ideas get standardized and canonized into culture with the I Ching, Confucianism, Taoism, the Naturalist School of Yin-Yang, 5 Element Theory, and more.

The basis of Chinese philosophy, and therefore basis of Chinese medicine, is that the Human Body, Earth, and Sun are an integrated whole. These are the Three Treasures, the most ancient Chinese system of correspondences used to order the cycles of creation, life, and death. Earth has its unique materials and processes: it nourishes us, it is Yin. The Sun has its own energy and role in existence: it governs us, it is Yang. The Body is the connection between Heaven (Sun) and Earth, it is what heaven and earth creates. Life is created by the uniting of these two energies, Yang and Yin. By understanding life’s relationship to Yin (matter) and Yang (energy), we can foster health, fight suffering, and create balance. Chinese philosophy and medicine starts here and moves onward to the beats of clinical experience and the imagination to understand and script what was witnessed. Formed in an age thousands of years before telescopes and microscopes, Traditional Chinese Medicine is a storyteller’s understanding of the human body and its relationship to nature.

Like its philosophical foundations, Traditional Chinese Medicine is based on observed evidence and experiments. I argue that the language we use to interpret this evidence is largely besides the point. From the very beginning, ancient Chinese medicine and philosophy has started with the truth and worked backwards — what, why, then how. TCM is a collective investigation on how to live long and die happy that has been taking place over several millennia. As a result, the practice is an art form with many styles, many interpretations of what “works.”

The ancient Chinese saw the universe as order and observed nature to try and distill that “Universal Wisdom” into philosophy and medicine useful for mankind. The first model of those findings is the I Ching. I am not afraid or ashamed to admit that the medicine I practice once attributed disease to demons and prescribed singing songs to the earth for treatment. EMBRACING CHANGE is precisely what the I Ching, “The Book of Changes,” teaches. It is because we evolve that we become so powerful. Chinese medicine and philosophy offer ways to understand and work with the flow of evolution.

Chinese medicine has never started over. Over the course of nearly 4000 years, “shamans” took what worked, left what didn’t, and eventually became doctors. With the right understanding, the truths of past, present, and future all fit inside the same box. This is the essence of the I Ching.

I Ching | The Book of Changes

The I Ching (Yi Jing) is one of the world’s oldest books. The I Ching consists of 64 hexagrams and their meanings. As we will discuss later, the hexagrams are six lines stacked on top of each other meant to symbolize a different phase of nature. Of these hexagrams, Jung wrote,

“The hexagram was understood to be an indicator of the essential situation prevailing in the moment of its origin. These interpretations are equivalent to causal explanations.”

In other words, the hexagrams were designed as pieces of the total reflection of the universe to offer a way to calculate the laws of change to work with their probability. In western terms, the I Ching is a way to communicate with our subconscious (which is a part of nature itself).

The way in which these hexagrams “change” into each other is called a “sequence.” The oldest surviving sequence of these hexagrams is the King Wen Sequence. While its true age and author are unknown, the sequence is often given credit to King Wen of Zhou (1112–1050 BCE). Most scholars agree that the assembly of the I Ching in its current form took place between the 10th and 4th centuries BCE, however variations of the I Ching can trace back to the 15th century. During the Western Zhou dynasty (1045–771 BCE), it was used for divination and practical advice. Like the creation and sequence of the hexagrams themselves, the sortition method of “casting” the I Ching is a mathematical structure meant to mirror the probability of nature.

If any of this starts to sound supernatural, it is helpful to consider the I Ching in the same way one might consider the Golden Ratio first calculated by mathematicians in Ancient Greece (~300BC). According to Wikipedia, of the golden ratio, Mark Livio wrote, “Biologists, artists, musicians, historians, architects, psychologists, and even mystics have pondered and debated the basis of its ubiquity and appeal. In fact, it is probably fair to say that the Golden Ratio has inspired thinkers of all disciplines like no other number in the history of mathematics.” Many people dismiss the I Ching as supernatural or pseudoscience despite the fact that, like the Golden Ratio, its origins are intended to be as natural as possible — it is a study of what is already occurring.

The genesis of the 64 hexagrams shouldn’t feel far out, it should feel familiar.

Each hexagram is constructed of two trigrams, or Gua. There are Eight Trigrams total. Each trigram (gua) is composed of three lines (yao). Each line is either whole (yang) or partial (yin). All of these specifics play into the mathematical structure of the I Ching. Connected but not limited to I Ching numerology, each gua represents a particular condition of our material universe — Heaven (or Sun), Lake, Fire. Thunder, Wind, Water, Mountain, and Earth. These are called the Ba (8) Gua. The I Ching’s 64 hexagrams are constructed by all the ways that the Ba Gua can interact with each other (8x8=64). They “interact” by stacking one on top of the other — there is a bottom trigram and a top trigram (yin and yang). All together, these 64 interactions reflect all sides of change and their interpretations offer counsel on how to work with those changes.

During the Warring States period (475-221 BCE), the I Ching developed into a cosmological text that was supplemented by a series of philosophical commentaries called The Ten Wings. The I Ching became canonized as one of the Five Classics of China in the 2nd century BC and has been highly debated and discussed ever since (quite a bit longer than the Golden Ratio, Mr. Livio!). I actually love how the I Ching became both a cosmological calculator and scholarly textbook at basically the same time in history. To some, a guide to the spiritual. To others, a guide to the material. Like nature itself, the purpose of the I Ching is up to its user.

Heaven. Lake. Fire. Thunder. Wind. Water. Mountain. Earth.

Consulting the I Ching creates a moment of synchronicity, a particular answer for a particular question.

When defending his use of the hexagrams in psychoanalysis, Jung wrote, “In the I Ching, the only criterion of the validity of synchronicity is the observer’s opinion that the text of the hexagram amounts to a true rendering of his psychic condition.” He continues, “I have always tried to remain unbiased and curious — rerum novarum cupidus. Why not venture a dialogue with an ancient book that purports to be animated? There can be no harm in it, and the reader may watch a psychological procedure that has been carried out time and time again throughout the millennia of Chinese civilization, representing to a Confucius or Lao-the both a supreme expression of spiritual authority and a philosophical enigma.”

As Jung indicates here, the ancient Chinese looked at their answers of the I Ching as intelligent. The yarrow sticks used in the divination casting are believed to be animated by “shen,” or spirit. To some, that means the spirit of nature. To others, it means our subconscious.

Whether you choose to understand this literally or metaphorically, it is important to realize that the practical use of the I Ching is like finding use in art. It is all entirely subjective and entirely important for self reflection and transformation. The argument for the I Ching is that this artistic understanding of philosophy and medicine is a special perspective. What other book from 4000 years ago is just as valuable today as it was then?

Jung, once again, puts it best. “The changing opinions of men scarcely impress me anymore; the thoughts of the old masters are of greater value to me than the philosophical prejudices of the Western mind.” I couldn’t agree more.

Confucius (551-479BCE) so valued the I-Ching that he called it “the perfect book.” Its teachings were a major influence in Confucianism and he taught it extensively in his university. The other major philosophy born from the I Ching is Taoism, which we see borrows its reliance on balancing nature through opposites and the importance of humility, sincerity, and moderation. The I Ching is also where Yin and Yang were first taught, no question the original philosophical backbone of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The ripple effect of the I Ching’s teachings is clearly seen in many philosophies of the Far East, such as Buddhism. Furthermore, the I Ching has played a significant role in how Western thinkers like C.G. Jung and Alan Watts first interpreted Eastern philosophy.

It is hard to overstate just how important of a role the I Ching has played in philosophy and psychology. The Sun rises in the East… To me, our western thoughts are truly in the shadow of eastern thinking.

Ancient Thoughts for Modern Times

In ancient times, it was said that the Eight Trigrams (Ba Gua) were discovered by Fu Xi who observed them on the back of a tortoise shell (sometimes told as dragon bones). Fu Xi and his sister, Nuwa, are known as the “original humans” in Chinese mythology and were the creators all things. In researching for this article, I was surprised to see ancient depictions of Fu Xi and Nuwa as snakes spiraling upward like the double helix of DNA. Considering their roles in Chinese mythology, this synchronicity is fascinating. It reminds me of Jeremy Narby’s exploration of shamanism and molecular biology in his book The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge. Ancient Chinese medical theories and amazonian shamanistic approaches to pharmacology seem like an apt comparison. Both of these primitive healers from opposite ends of the globe have been tapped into the healing effects of plants and herbs in ways western pharmacology is still catching up to. This is further evidence that visions and legends have effective real world applications.

According to The Great Commentary, another one of the 5 Classics of China, Fu Xi observed the patterns of the universe "in order to become thoroughly conversant with the numinous and bright and to classify the myriad things."

From these observations, Fu Xi (or the collective voice he represents) gave us the Ba Gua and the 64 hexagrams. These patterns have correspondences in numerology, astronomy, astrology, geography, geomancy, anatomy, human relationships, martial arts, Chinese medicine and more. The intention of these correspondences remains the same — so that we may become totally familiar with how the universe unfolds. The I Ching provides the What and the Why, it is up to us to come up with the How.

Ultimately, it is how we use the I Ching that determines its value. Like Chinese Medicine and Philosophy themselves teaches, both yin and yang are required for growth and life. In order for our health and happiness to thrive, we must maintain balance between ancient and modern, east and west, nature and technology.

Acupuncture and eastern traditional medicine is not meant to replace your MD. Neither is the I Ching supposed to replace advice from reason or your parents. Rather, the lesson here is to INTEGRATE the whole.

Be The Change.

The I Ching is an attempt to reflect the entirety of our existence — Heaven, Lake, Fire, Thunder, Wind, Water, Mountain, Earth and all the ways these forces interact with each other. The 64 hexagrams are designed as a microcosm of the entire universe and their meanings are a system of universal correspondences. When you understand the hexagrams, you understand nature.

Of course, all of this is reductionist. This is the point! The I Ching shows us that the truth is already out there. In evidence based medicine, we start with the what work and go backwards from there. Eastern Traditional Medicine and philosophy is deep. It is ancient! It is primitive. It is also extremely useful. They are based on evidence over thousands of years of clinical experience. Explaining how these things work is only an afterthought. Did not the Earth form before consciousness?

While most cleromancy is aimed at supernatural intervention, the I Ching is attempting to tune us into reality, not out of it.

If we are in harmony with Earth and all of its wisdom, we do not stumble blindly into the night. The future is uncertain, always. However, the past is a pure reflection. We must always exist in reality. Our pursuit of new evidence should not be cavalier. As we journey into the future, we should surf the momentum of our entire human history. There is so much we already know. We must use this knowledge! Beyond that, everything possible that we do not yet know is already figured out for us by the universe — it will only take time to uncover the truth of how it will be done.

Gravity existed before its laws were discovered by Sir Isaac Newton. Like Newton, we must consider all our knowns and unknowns then PRACTICE / TAKE ACTION / EXPERIMENT. If we do not triangulate ourselves between the past, present, and future, we will get lost, hurt, or both. In a world where the only thing constant is change, right wisdom and right action allow us to sync to the flow of universal truth and good.

My whole intention in writing this article is to hopefully pave the way for us to reclaim the I Ching as a useful reflection of our human existence. I hope that it gets us out of our heads and out of the algorithms. I want to inspire everyone reading this to use it. We are in an era now where truth is hard to come by. “Good advice” is getting more and more obscure. In modern times, everything changes so quickly, it is often hard to keep up. In a lifetime as young as ours, the I Ching carries a certain weight to its wisdom that is rare to find. Its teachings are tried and true. At the very least, it has inspired philosophy and medicine that truly works. Like our elders and ancestors, it deserves our respect. The I Ching does not need us to “believe” in it, it already exists in a powerful way. In fact, when you look at it the right way, you see that it always has existed. It always will!

“It is not for the frivolous-minded and immature; nor is it for intellectualists and rationalists. It is appropriate only for thoughtful and reflective people who like to think about what they do and what happens to them.”

- C.G. Jung

When considering what to write in his forward to Willhelm’s I Ching, Jung consulted the oracle itself. From its answer, Jung wrote that the “[I Ching] conceives of itself as a cult utensil serving to provide spiritual nourishment for the unconscious elements or forces that have been projected as gods — in other words, to give these forces the attention they need in order to play their part in the life of the individual. Indeed, this is the original meaning of the word ‘religio’.”

The I Ching is our opportunity to reclaim prayer. But what do we make of the answers to these prayers? Jung continues,

“I agree with Western thinking that any number of answers to my questions were possible , and I certainly cannot assert that another answer would not have been equally significant. However, the answer received was the first and only one; we know nothing of other possible answers. It pleased and satisfied me. To ask the same question a second time would have been tactless and so I did not do it: “the master speaks but once.’”

Like a prayer to god, the signifance of casting the I Ching is not in who or what is being acknowledged, but in the act itself. The I Ching is one of many tools to communicate with the subconscious, one that I argue is highly reliable and practical compared to other languages and rituals.

I have spent this entire article expanding on the I Ching as a mirror of the whole universe. In closing, I should try and be more specific. The I Ching is a reflection of YOU. What you see and what I see is different. This is the point.

One should not expect the I Ching to foretell what is going to happen, especially in specific terms. Rather, remember how the book gets its namesake: The Book of Changes. The I Ching gives advice from the subconscious on how to approach the future and how to reflect on the past. In between past and future, in between the I Ching, is YOU.

You are the beginning, middle, and end of truth, not the book! It is always you. See yourself and know yourself. Understand the situations you are in. There are ways to go from here. Be the change.

Back to the Beginning.

Like I told you, I tend to say and do too much. In closing, rather than spend any longer on the subject than I already have, I’m going to bring it back to the words of Frank J. MacHovec, the author of my very special translation of the I Ching.

How can you use this book? Read it as is and ponder its advice or as a kind of horoscope, a source of advice for the future, its original intention.

The object of this [translation] is to provide you with the I-Ching in simple modern English. English headings have been changed to better match the content of the passage. The passages themselves have been rephrased. It is hoped this version avoids the awkward 18-19th century language and the deep scholarly analysis of other works, for such is not in keeping with Chinese ideal of natural simplicity. But this introduction is too long! Spend your time in queit contemplation of the timeless I-Ching, not on the thoughts of unworthy writers who die and are forgotten. Let this be “the writer’s hexagram” and number it significantly, 0.”

— F. J. M.

The I Ching is yours now. Use it. See yourself in it.

For a deeper look at the hexagrams and their meanings, visit this site